Diving with a disability

A scuba diving training program is changing lives for people with disabilities who are swapping wheelchairs for water.

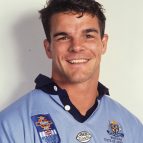

Mark Slingo had just qualified as a diving instructor in Thailand when he had a fall from a balcony that left him a paraplegic. ‘My boss said “Why don’t you come back to work to see if you can still teach?” – ever since then I’ve been trying to get more people in my position to enjoy the benefits of scuba.’

Mark is one of the board members of Disabled Divers International (DDI), a non profit organisation that conducts disabled scuba diving training programs for professional and nonprofessional students. So far he’s taught 200 instructors around the world how to teach disabled learners to dive.

In the training Mark includes an introduction to different conditions including Cerebral Palsy, spinal injury and Downs Syndrome but he keeps it brief. ‘Everyone is different as to what they can and can’t do so it’s important to treat each disabled learner diver as an individual.’

For people who are wheelchair bound, diving is exhilarating, Mark says. ‘There’s nothing like it.’

‘We call ourselves life changers because you see the change in people who think they can’t do it and they do it and get this huge sense of achievement. So often people with disabilities get messages from people around them about what they can’t do.’

Awareness of the positive health and social benefits of diving has increased dramatically over the last 20 years with both the US and UK military adopting it as a part of their rehabilitation program with disabled veterans and people who’ve been in combat. ‘There’s a real interest from dive professionals wanting to run these sorts of programs. And because Australia is one of the best diving places on earth Aussie dive teachers are very keen,’ Mark says.

The teacher

The teacher

Ash Payne of Perth’s Dive Unlimited was inspired to take up DDI Instructor training after one of his student’s friends who was in a wheelchair came along to watch them dive. ‘He said, ”I wish I could do that!” and I thought, “Why can’t you?”’

In 2015 Ash undertook the first DDI Instructor Training course in Australia with Mark Slingo. It was a great experience, Ash said, but the real learning was in running his first class. Held over three days, with one day in a pool and two days in the open water, the class attracted six students.

As a swimming teacher and a dive instructor Ash had plenty of experience teaching a wide variety of people, and adapting and modifying his techniques. But running a class for people in wheelchairs was a ‘hell of a learning curve. It was like the first time I’d taught able bodied people how to dive.’ Ash thinks he’s a better teacher as a result. ‘Beforehand my approach was to outline the steps, do this, then this, then this. But all that goes out the window when you’re teaching people with mobility problems. Now I’ve become more focussed on how individual people pick up things.’

Ash says diving is a great way of getting some exercise as well as having fun. ‘You can go diving for a whole day and spend maybe 2 hours in the water. The rest of the time is spent chatting on shore, having coffee together before the dive, or going to the pub afterwards so it’s a very social hobby.’

The Learner

Cassandra Burrell grew up spending a lot of time at the beach and always wanted to be a marine biologist. But a mitochondrial disease means that since age 7 Cassandra’s been in a wheelchair.

Not that that’s stopped her enjoying sport. She’s an active member of the WA Wheelchair Sports Association and has enjoyed competing in boccia, swimming and field events. She now does archery and scuba diving.

She’d always wanted to try scuba diving and recent developments in accessible equipment and training courses have made it a much more inclusive sport.

She did her training with dive instructors Ash Payne and Kamila Opon and said the course was excellent. ‘They adapted their teaching and really catered to my needs.’

Graduating from the swimming pool to the ocean was really exciting Cassandra says but the dive was almost derailed because the water pressure was making her ears ache. ‘I didn’t think I was going to get too far down there because my ears were playing up. I had to keep going up towards the surface to equalize them, back and forth for about ten minutes.’

But it was all worth it. ‘The freedom that you feel with no weight, the peace and tranquility are just beautiful. I swam past the same reef maybe ten times and each time I’d see something different.’

She’s done another three dives since then and each one gets easier, with less to worry about as she develops confidence.

Buoyancy has been the biggest problem. ‘The biggest challenge was the buoyancy vest but after two sessions I’d worked on my technique. Relying on just your arms and hands to swim is tricky too because you don’t want to disturb the sand or you don’t see anything.’

‘The first two dives someone is with you the whole time, practising things with you that you’ve learned in the pool like taking your mask off; taking your regulator out and retrieving it; checking depth and air gauges and practising hand signals. By the third dive, things are easier to remember and you can concentrate on swimming and looking at what’s around you.’

‘We went to Rockingham Beach which has a dive trail where they’ve put in a plane and a boat that’s covered with coral forms. Swimming round the reef I saw a school of 40–50 pearl coloured fish, seahorses on the lines, and crabs walking on the sand. I had to remember not to hold my breath and keep breathing!’

Cassandra has to space out her diving because it takes a toll on her physically but she says it’s worth it. ‘I’m quite happy to just conk out for a couple of days afterwards.’

Next up Cassandra would love to explore further afield, diving at Rottnest Island, or doing some night dives. And hopefully seeing some sharks in their natural environment.

See the full issue of Quest 1, 2016