Indigenous learnings

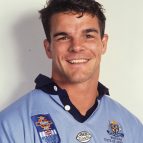

Charles Darwin University researcher Tracy Woodroffe is exploring ways that non-Indigenous educators could benefit from understanding Indigenous knowledge systems and approaches to education.

Tracy Woodroffe knows what it’s like to be an Indigenous teacher and an Indigenous student. She has 20 years experience as a teacher, working in early childhood, primary, secondary, and tertiary settings, as well as in Indigenous education. Currently she’s a student too, completing her PhD at Charles Darwin University.

‘In my work and particularly in my work with pre-service teachers and improving teacher practice, it struck me there was often this disconnect between non Indigenous teachers and Indigenous learners. I began to wonder about why this might be and it became the starting point of my PhD.’

‘Non Indigenous teachers tend to look at their students through a Western frame of reference. Too often Indigenous people are measured in terms of white knowledge and skills and are evaluated against Western versions of success.

‘I came across the work of Indigenous educator and academic Karen Martin who talked about ‘Indigenous knowledge’ and that really hit home. It seemed to fit with something I had been trying to articulate, something that had puzzled and concerned me. How can we forge a link between Western and Indigenous knowledge as educators? If we could do that it seemed to me we could enhance both teaching and learning.’

Tracy says that too often teacher training fails to recognise the influence of a learner’s culture and how it influences preferences in learning, and what is valued about classroom experiences. Her PhD research is a chance to redress what she feels is a glaring problem in Australian education. Understanding a learner’s culture – how they relate, and what they value about knowledge and education – is essential if teachers want students to get the most out of the learning experience.

Tracy has adopted Martin’s definitions as a theoretical framework to highlight the links between Western and Indigenous values when it comes to knowledge and learning. Tracy hopes that building bridges between teachers’ and Indigenous learners’ knowledge will transform both teaching and learning.

She says although educational expectations of teachers and students can be very different, it is the similarities between them that are a fruitful path for improving educational outcomes. ‘My PhD research is starting to show that non-Indigenous pre-service teachers want to make a connection with Indigenous students, but in reality it can be quite difficult,’ she said.

Tracy is teasing out the contrasts and the similarities between Western and Indigenous ways of being, ways of knowing and ways of doing. ‘What I’m hoping to do is improve teacher training by highlighting the limitations of the Western viewpoint, and the potential of a more inclusive educational approach.

‘Too often Indigenous people are referred to in terms of deficits. Seeing Indigenous people in a deficit light doesn’t help anyone.’

She believes that making changes so teachers value and understand Indigenous approaches, knowledge, and culture will improve Indigenous students’ experience of education and learning.

‘I’m aiming to engage in research that can be used across Australia. The key is developing Indigenous pride in and respect for the importance of our own ideas and Indigenous knowledge.’

Tracy’s excited to be presenting her research at the world’s largest Indigenous education conference, the World Indigenous Peoples Conference on Education in Canada in July.

‘It is exciting for me as an Indigenous person to have this opportunity to connect and share ideas with other Indigenous people from around the world,’ Tracy says. ‘My abstract was picked up and accepted really quickly, which indicates that my research is addressing a real gap. What’s been missing in educational research is the Indigenous voice.’

See the full issue of Quest 2, 2017