A new family learning program shows that helping with homework improves communication between refugee parents and children.

After school on Mondays and Tuesdays, a group of families speaking any one of a number of languages – Tamil, Hindi, Arabic, Burmese – arrive for a two-hour class at the William Langford Community House in suburban Perth. The parents go to one room, the children go to another. They are part of a successful homework program involving refugee kids and their parents.

Children whose parents have low literacy and numeracy skills are less successful at school. But the problem’s even worse for refugee families. Poor English, isolation and unfamiliarity with local services and the school system makes it hard for parents to help a child who is struggling academically.

The demands of settling into a new country and trying to put an often traumatic past behind them are often much larger worries for newly arrived refugee families.

Breaking the cycle

The Families Learning Together Project, a new intergenerational program, is aiming to break the cycle. It aims to improve parents’ literacy as well as their understanding and engagement with the education system as a way to improve their child’s school performance.

Four community centres in remote, regional and metropolitan WA have run a pilot program. The pilot was so successful that five more centres are rolling the program out this year.

The idea for such a program was sparked during a brainstorming session three years ago at a Perth meeting of librarians and community groups. Maria Cavill, manager of the William Langford Community House who was at the meeting was concerned about asylum seeker and refugee children experiencing difficulties with school. And she was looking sponsorship for a program to do something about it.

‘The parents priorities are how to survive, how to recover from and overcome psychological trauma and move on. The kids are trying to do the same and often their schoolwork is suffering. But because their parents don’t understand the Australian curriculum, the kids are often struggling on their own.’

Pilot centres selected across WA

Linkwest, the State Association for Community, Neighbourhood and Learning Centres, with funding from the Office of Multicultural Affairs, selected William Langford Community House as one of the four centres to run a pilot.

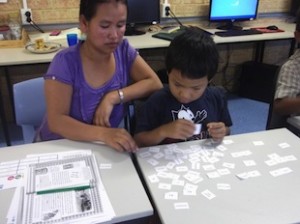

Using the curriculum developed by Linkwest as a guide, tutors teach the parents about the Australian education system and practical strategies to help them with their children’s schooling. As well as offering help in literacy and numeracy – around half of the parents can’t read or write – tutors take the group to the local library and link them to services in the community that can help their child.

Building trust

Maria says the biggest issue has been gaining parents’ trust. ‘Most refugees who have come through the camps have developed a mistrust of NGOs. So when they first arrived for classes they were very wary and didn’t talk much.’

‘Many of the parents are isolated. They don’t know who to ask for information or who to approach. They don’t even approach their neighbours.’

Finding a common language was also tricky, with people from Sri Lanka, Burma, India, China, Afghanistan and Sudan. ‘Their English was very broken but halfway through they started to open up and make friends with other parents. Now they walk together from school to home and ask one another questions about homework.’

Benefits for both parents and children

Progress is slow in terms of the adults’ literacy, Maria says. ‘But it’s getting there.’ Ninety per cent of parents have joined free English conversation classes at the centre as well as art and craft classes.

Maria notices big changes in the communication between parent and child. ‘Because of the trauma these families have suffered and their often horrendous experiences before they arrived in Australia they have stopped talking. It’s a big step to see them sharing and discussing things together.’

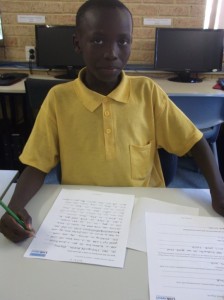

When a parent can’t read or write English, a child often becomes the family interpreter, missing school to attend appointments with their parents at the doctor or to agencies like Centrelink. Children often take on the role of adult and tend to think of themselves as smarter than their parents, Maria says. But in this program the emphasis is on helping each other. ‘A child might discover his mother is quite good at numeracy and can help him out. The parent might then be able to ask the child for help understanding a word.’

One Sri Lankan woman and her son attended every session in term 1, and then returned again in term 2. ‘The mother was very shy. She had no English. After joining English classes she became a volunteer at the centre. She helps with the after school kids program and helps prepare material, uses the computer, types out plans. It might seem routine or menial work to us but to her it’s a very big thing. Her relationship with her son is getting better. At the start of the year they were very reserved with one another. Now they talk to each other and make jokes. It’s healthy.’

‘When people have been through horrific circumstances they go into their shell. It takes time for them to start to trust people. You can see this change in her but you can also see it in her son. He now comes along to the after school activity program and is joining in much more with the Australian children.’

Developing the ‘Families Learning Together’ curriculum

Mihaela Nicolescu, centre development officer at Linkwest, says the project’s lessons plans for both children and parents, supporting material and handouts that were developed by qualified teachers, had to be both comprehensive and flexible.

‘It was a challenge because it certainly is not a ‘one size fits all’ approach. Parents differ not just in terms of their skills in literacy and numeracy, but in their formal qualifications. For some parents their own literacy and numeracy skills are quite low while other parents may have completed higher degrees. Then you need to take into account different learning styles, and differences in the amount of information and understanding they have of their local education system.’

Personalising resources so that they were relevant to each group was critical, as was finding tutors who could facilitate and adapt the material for their local group. ‘Tailoring the program to ensure parents don’t feel it’s patronising, or that they are being taught things that are basic is key’, Mihaela says. Linkwest also developed a facilitation course so that centres who took part could run the course well.

Feedback from pilot shapes future plans

The practicalities of running the pilot gave Mihaela and her team useful feedback. The requirement that families involved have been in Australia for two years or less became a hurdle. ‘The first two years in a new country are very demanding for a family and the feedback indicates that those who’ve been here longer benefit the most.’

Secondly, the age range of the children presented challenges. ‘There’s a massive difference between an 8 year old and a 12 year old. It isn’t age as much as the differences in literacy levels that is important.’

Program successful in effecting change

As a result of the courses, all parents felt more confident giving help with homework and children were more likely to ask for it. As a result, children in the program are doing better at school. ‘If parents encourage children to learn by learning with them it creates a positive culture that’s essential to the children’s success.’

Mihaela says the pilot has reinforced the potential of programs like this to effect change not just at an individual or family level but to society at large which benefits from the social effects of improved school participation and improved literacy and numeracy. ‘The potential is huge, the interest is huge, and the research on intergenerational learning is very encouraging.’